Asking 5 big questions can raise the value of personal experience

Sometimes they call learning by experience “The School of Hard Knocks.”

Going at something blind without the benefit of someone else’s experience can be painful.

They also call it experiential learning. “Hard Knocks” sounds like a painful way to learn something. It can be. It doesn’t have to be. Experiential learning is the best way to learn something. Not only does it communicate the information, but experience illustrates its worth.

Knowledge is a possession. With any possession, it’s best to appreciate its worth.

By three methods we may learn wisdom: First, by reflection, which is noblest; Second, by imitation, which is easiest; and third by experience, which is bitterest. — Confucius

A teacher can tell, and a teacher can show. Telling is abstract. You’re listing the reasons and expecting your audience to make the connection with what they’re doing.

On the other hand, showing is vivid. Not only are you relating the information, but you’re connecting why it’s important.

Teachers are often limited in their ability to demonstrate their lessons. Where the “faculty” at the School of Hard Knocks excels is in their ability to show and demonstrate.

Never mind understanding the lesson, sometimes surviving the lessons are a challenge.

That’s another way of saying that tuition can be costly.

The school of hard knocks can teach more than you wanted to know…

Being good at learning from experiences isn’t a guarantee that bad things will never happen to you. What it is, however, is a way of getting the most you can from what happens to you.

A graduate student in his twenties was standing on the side of a dirt embankment. He was on a hike with friends, enjoying some beautiful spring weather in a state park in Texas.

Suddenly, the loosely packed earth underneath his feet gave away. The man found himself plummeting 25 or 30 feet down the side of a gully into a ravine.

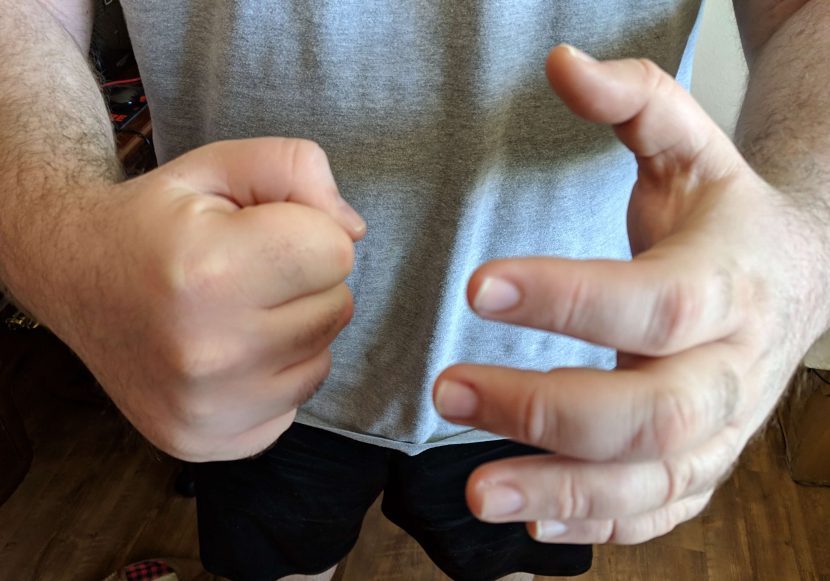

While tumbling down the hill, he instinctively stuck his arms out to break his fall.

The young man’s instincts were right. His arms saved his unprotected skull and head—nobody hikes with a helmet.

Unfortunately, with the fall, many small and large bones in his arms and hands shattered and broke.

Medics took him to the nearest emergency department, almost 100 miles away. X-rays showed the doctor, the young man, and his friend precisely what and where his arm bones were broken.

A few years before, the man had had an anatomy class. Unfortunately, much of the information he had learned was rusty and underused.

Between the pain medication, the anxiety, and the stale knowledge base, the young man struggled to understand what the doctor was telling him.

His plans for the next few months would be undergoing significant changes. He was still coming to terms with the changes in the emergency department.

Part of it was if his class was like so many anatomy classes someone might take at a university. A professor had stood at the front of a classroom and lectured about the names of the bones and how they were connected.

Most of the students listen as they’re half asleep. He was undoubtedly one of them, coping with the mornings with a tall cup of coffee or an energy drink. The professor’s lesson on the bones of the arms and skeleton lacks the immediacy of the young man learning what kind of rehabilitation he would face.

In the former situation in the classroom, there’s no stress, but it’s abstract, and many people will find it boring. They need a bunch of caffeine to make it through. In the latter situation, there’s the shock your next few months aren’t going to be what you thought.

We wouldn’t want a society where professors of anatomy went around breaking students’ arms to demonstrate the importance of knowing the names and articulations of the bones in the arms. We don’t need to fall off a cliff to understand the kinematics of the injury to bones. That would be crazy.

When we’re talking about personal development and people helping themselves, we want people to learn well from every avenue available — lecture, reading, and, of course, experience.

We want to learn more from our experiences, even the ones that aren’t so life and plan-changing as a fall down a tall cliff. We want to lower the cost and increase the value of what’s learned.

Today, the young man who fell off of the cliff can tell someone who has broken their arms all about the recovery process from healing from multiple fractures. He knows the feelings in detail.

Yet the cost of the knowledge, one can argue, was too high, especially when he wasn’t going to be working in a position where he’d regularly encounter people with multiple broken bones.

He could have learned much of the same without falling from a mountain.

Being curious is key.

Tuition at the School of Hard Knocks can be expensive

To fully understand what had happened to him and what the future held, the young man has to know what bones he broke, how those bones are supposed to interact with his other bones, and the type of fractures he had.

Additionally, he needs to know how long it takes bones to heal, what kind of surgeries he’s going to need, what kind of rehabilitation he’s going to face, and how to cope with the pain.

There’s going to be a lot of pain.

He’s also going to have to know how to use his arms again. If his friends hadn’t helped at the scene, and if the park medics hadn’t known what they were doing, he could have ended up with artificial limbs. They made sure the blood was circulating and that he was able to keep his arms.

The fall into the ravine demonstrated the importance of this knowledge like nothing else.

While a college anatomy class wouldn’t have taught him everything about the course of his recovery, it would have gotten his understanding a good way down the road.

The tuition in his case was rather expensive: several months of rehabilitation, pain, inability to work, and delay in completing the coursework for his degree.

Sometimes the School of Hard Knocks is like that.

Yet experiences can be both minor and major.

You can learn a lot from both.

Sometimes a minor experience can provide a major lesson.

For example, you’re hungry. You decide to eat a heaping plate of leftover spaghetti and immediately head off to bed.

A half-hour later, you wake up gagging and coughing. The spaghetti has come upon you, and you’re choking. Spaghetti is dense food. It takes a while to digest. Not only that, but your stomach will be churning while you’re trying to digest the food. You’re laid out flat. The food can easily push past the sphincter that holds food in your stomach.

There are a couple of things you could have done differently. You could have eaten something easier to digest. You could have waited a bit longer before lying flat. Either action could have helped.

Once you recover, if you adjust when you eat or lay down, you emerge no worse for it.

If the experience doesn’t kill you, if you don’t suffer significant losses, if you retain the lesson no worse for the wear, and you move on without too much mental or emotional trauma, then the lesson is a bargain. You have a vivid illustration of why it was important.

Merely changing a thing or two about when you eat a heavy meal can save you from getting on medication for acid reflux that could lead to you getting surgery eventually.

Regularly reflecting on your lessons at SHN (the School of Hard Knocks) can prove to be a bargain.

Organize your lessons at SHN

The whole problem with learning at SHN, or learning by experience, is the lessons aren’t organized.

Organization is half the battle to getting anything done.

You are your teacher at the SHN. If you don’t take the time to reflect on what you’ve learned, you’re likely to make the same error again.

On the other hand, if something went right, it will only go right by accident again.

You very well might eat that plate of spaghetti again the next night, messing up your sleep one more time.

Philosopher George Santayana succinctly said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Santayana spoke of big events: wars, facism, and things like that.

His insight can and should be applied to minor events, like a guy overeating spaghetti and heading off to bed.

A good teacher, coach, guru, or whatever, will take you step-by-step through the material. He or she will summarize the material. Later he or she will check your memory. At the end of the course, there will be a final exam.

To learn the most you can from your experiences, you’ve got to do the work of a teacher (or be a coach) for or to yourself.

Recruiting better faculty at SHN

In the military, education is called “training.”

Yet there’s a subtle difference between education and the military idea of training.

Education takes place in the classroom. The subjects are more abstract. For example, you might learn the theory of how a rifle works and why it’s essential to keep it clean.

Later, you’re going into the field. You’re going to get to fire the rifle. You’ll experience how your ability to control your breathing affects the aim of the projectile. You’re going to learn how to clean your rifle and what it takes to get your weapon in shape to pass the critical eye of the armorer.

You’re going to have training missions.

The way military leaders make it into education is to sit the soldiers down who have just trained and have a discussion session called an after-action review. It’s so common in the military that it’s commonly known only by its initials: AAR. Of course, the military is big on acronyms for everything.

This is what’s missing from the way most people learn from experience. It’s a step that’s important enough that you should take it when you’re trying to help yourself get better at anything.

The personal AAR can lower the cost of tuition or increase the value of the education received at the School of Hard Knocks like nothing else.

It comes down to asking five questions about any project or test you do when you’re trying your situation or yourself.

- What did I think was going to happen? (Past)

- What did happen? (Present)

- What went right? (Positives)

- What went wrong? (Negatives)

- What should I do next time? (Future)

The guy trying to learn to sleep better might do the same thing after he wakes up in the morning.

He’d review his sleep session.

He’d ask himself the five big questions:

The 5 Big Questions

1. What did I think was going to happen?

I thought I’d go to bed and wake up in the morning. Maybe I’d get up in the middle of the night to use the bathroom once. If I did, it would be no big deal. That’s what I do when I eat right before bed.

2. What did happen?

About a half-hour later, I ended up choking and gagging. I had to spit up the noodles and meatballs from the spaghetti. Then it made my throat sore. I couldn’t get back to sleep right away.

3. What went right?

I didn’t choke or suffocate. I was able to breathe, though it was hard for a bit.

4. What went wrong?

I couldn’t digest the food right away.

5. What, if anything, should I do differently next time?

When I go to bed next time, I should either wait a bit before laying down or eat less. I could also eat something besides spaghetti that’s easier to digest.

Honor Roll

People who talk a lot, who have an opinion about everything (the more outrageous, the better), and who are great at making everyone pay attention to them seem to have an advantage most of the time these days.

These people find themselves on TV on reality shows, on the nightly news, and in government. They amass large followings on Instagram. They make videos for YouTube that get tens of thousands of views. They’re invited to talk at seminars, conventions, and give TED talks. They tell stories with emotion that convey easy-to-understand points.

They’re great at running their mouths off. They rarely say, “I don’t know.” They have all of the answers and deliver them confidently, just like someone might jerk their knee reflexively.

People can understand what they’re saying, too, because it’s not hard to. Listeners don’t have to work very hard to understand, either. When it comes to the talkers and the listeners, there’s nothing profound or deep going on between anyone’s ears.

The opposite of these shallow “look-at-me” types have the advantage at the School of Hard Knocks. They’re the type to think about their experiences. The five-part AAR process might be something that occurred to them naturally. Either that or they adapted it from a leadership class. That’s all it is, really, self-leadership.

While there is a clear advantage to being like the former individual, being a contemplative person helps you learn lessons from your life, your experiences, what you read, and from talking to other people.

Some of them, undoubtedly, have learned to act as the former individual because it’s so profitable in today’s society and yet, on the inside, be contemplative and learn from their experiences.

Learn from others’ experience

Simply put, review what you can from failures and successes others have had. You can use the AAR format as a way to show interest in what they’re telling you. Generally speaking, people are often willing to teach and know if you only show interest in them as a person.

When you’re reading, use the bookmark tool on your browser or a service like Pocket to bookmark articles across your devices to refer to later. A good practice is to review these articles one day a week to retain this good information and to keep it at the top of your mind.

Review and organizing are as much of a key to learning and success as something like keeping your eye on the big picture.

Learn by keeping a dream journal

Finally, writing your dreams down can help you understand what’s going on in your life. It enables you to get in touch with your feelings and gain insight into many aspects of your life.

Someone who keeps a dream journal has a natural AAR every day. What he or she needs to do, however, is to try to learn from experiences. It doesn’t just happen. To even have a chance to do that, he or she needs to start remembering and understanding their dreams.

The heart, however, wants what it wants. Adventure. Security. Whatever it comes up with.

Reconciling and acknowledging the disparities between the subconscious and conscious mind is part of mindfulness.

That’s what makes dream journaling so powerful. It’s an easy way to know yourself. When you know yourself, it’s easier to help yourself.

If you can’t lower the cost of tuition at the School of Hard Knocks, you can at least increase the value the experiences by getting every single drop of value from them. Remember, the best way to do that is to think of the five questions:

- What did I think would happen?

- What happened?

- What went right?

- What went wrong?

- What, if anything, should I do differently next time?

Further Reading:

Having an out-of-body experience doesn’t make you special.

How to talk to others about your psychic experiences.

Your opinions form when you’re asleep and you should know what those opinions are.

Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

James Cobb, RN, MSN, is an emergency department nurse and the founder of the Dream Recovery System. His goal is to provide his readers with simple, actionable ways to improve their health and maximize their quality of life.

We use some affiliate links. If you click on a link and make a purchase, we may receive a commission. This has no effect on our opinions.