If you’re not willing to forget the notion that thinking about something doesn’t necessarily cause something to come into being or attract it to you, stoic mindset exercises aren’t for you.

Stoic exercises ask you to meditate on the worst things that can happen to you and those you love.

Is that depressing?

Yes.

During my week of stoic mindset exercises, hypothetical bombs went off; I imagined that people I cared for got into bloody car accidents, and I got into car accidents too.

In my mind, my emergency department was overwhelmed for a lot of different reasons. We couldn’t get supplies. Administrators told us to shut down; we insisted that the people needed us and we needed to do our best. We had multiple mass casualties. Water supplies failed, and I worked a 36-hour shift before dropping off from sheer exhaustion.

One bad thing happened after another.

Work was Hell, and my imagined life outside of work was hellish too.

I can be very creative.

While a friend miles away did get into a bad car accident during the exercise, there’s no real reason for me to assume they’re related. While we did work together more than 30 years ago, we haven’t worked together for years.

Stoic mindset exercises feel a lot like personal wargaming or contingency planning. They feel like mental preparation for doing something like hitting a ball in a batter’s or working on your golf swing. They squelch wishful thinking.

Positive thinking writers commonly assume thinking of the worse will paralyze one into inaction.

There’s a built-in assumption that you’ll get so depressed that you’ll freeze in the face of tragedy and misfortune.

Some people do. That’s not ideal or virtuous, according to the ancient Stoic philosophers. The mental exercises are meant to get you past this regrettable stage. Stoicism is meant for crushing anxiety.

Positive thinking compared to Stoic thought

Day-to-day modern thought runs fairly contrary to Stoicism.

Positive thinking is framed as avoiding negative self-talk. Stoicism, on the other hand, is more concerned with expressing virtue while confronting both positive and negative events and feeling the same way about both of them.

While the ancients did their best to remember that “this too shall pass” and that “they too will one day die,” positive psychology holds far greater sway these days. The Law of Attraction is one facet of positive psychology taken to a reasonable conclusion. According to the Law of Attraction, by visualizing success, money, or someone, the idea is that you can bring it into your life.

There are versions of positive psychology that come with and without religious thought attached. Positive psychology teaches ideas are causative, either through the action of the “universe” or “God.” Faith in yourself, in your ability to attract these good things into your life, is of the utmost importance. In some versions of positive psychology, you don’t even entertain negativity or skepticism.

The Gospel of Prosperity practiced by some ministers like Creflo Dollar and Joel Osteen and others are another branch of positive psychology.

A quintessential positive psychology book: The Power of Positive Thinking

The Power of Positive Thinking by Norman Vincent Peale sold 5 million copies, and it has a message that people like to hear. Other similarly successful books include The Prayer of Jabez (10 million copies, by Bruce Wilkinson), The Secret (30 million copies worldwide, by Rhonda Byrne), and The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success (by Deepak Chopra).

Much of the philosophy can be summed up like this: Imagine and really believe you can do it/ can get it. You’ll get it/do it.

Here are some steps Peale suggests one can take to build up their ability to have faith in themselves which will cause good things to happen to you and make you happy.

- Formulate and stamp indelibly on your mind a mental picture of yourself as succeeding. Hold this picture tenaciously. Never permit it to fade.

- Whenever a negative thought comes to mind, cancel it out with a positive one.

- Don’t build up obstacles in your imagination. They must not be inflated by fear!

- Don’t be awestruck by other people and try to copy them. Nobody can be you as efficiently as you can.

- Repeat Romans 8:31 ten times a day: If God can be with us, who can be against us?

- Remind yourself that God is with you and that nothing can defeat you.

And so on. The more faith you have, the more confidence you can have in yourself, and the more you can manifest, Peale suggests.

Some positive psychology comes dressed in scientific research. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi posits that a positive state of happiness can be found by setting challenges for oneself that are neither too difficult nor too simple for your abilities. Do that, and you’re likely to enjoy life.

Stoicism and anxiety

As a philosophy, a way of looking at the world, Stoicism is fairly different from positive psychology.

The emphasis is on happiness, virtue, and excellence rather than on obtaining material goods like money, career success, or love from another. However, in some modern iterations of Stoicism, it’s implied that thinking in this way leads to material success.

Much of the world is out of your control, Stoicism posits. The only thing in your control is your reaction to what happens.

Rather than putting effort into imagining yourself obtaining the objects you desire, you imagine the worst that can happen. Then, in the midst of the worst, you react with composure and virtue.

If you can’t change it or it’s not in your control, don’t worry about it. You only worry about affecting what you can.

The hope is that this leads to a certain sense of peace.

When you encounter a headline on MSN like this: Toddler dies after aunt pushed him into lake and watched him drown for 30 minutes, stoic mindset exercises would make you inclined to be emotionally unaffected by the tragedy when reading or hearing the news. You couldn’t have done anything about it. You weren’t there. It was out of your hands.

Yet the part that’s often forgotten or misunderstood about the stoic mindset is that it goes beyond just shrugging and saying much of the world is out of our control. You could have rescued the child if you were there on the scene. Maybe knowing about the child’s death is a reason to pay attention to the world around you. How would that have gone?

They urge you to rigorously consider what is and isn’t in your control. It’s called the stoic fork. One tine is for what’s in your power; the other is for what isn’t. The concept urges you to separate thoughts into these two different groups. What’s not in your control is irrelevant.

Unlike positive psychology or positive thinking, you go “there.” You absolutely do. There’s no wishful thinking involved. Yes, it can be unsettling to imagine the social approbation and the shockingly cold temperature that goes with plunging into Lake Michigan in September then, if the lunatic aunt levels some false accusation against you and causes you to lose your job and be slammed in the media—your word against hers. Oh, yes, that sucks! The boy survives in that alternate fake scenario, and justice is served.

Or your efforts go for naught. The boy still dies, and you’re on the dock freezing, a cold wind blowing.

My stoic mindset exercises for the week

It’s one thing to read about something; it’s another thing to apply it. Stoicism and the Art of Happiness by Donald Robertson has a number of these exercises, and I selected seven of them to make Stoicism part of my worldview. Afterward, I reflect on my feelings and what I learned.

-

- When I made plans, I added, “God willing.” I don’t have complete control over whether those plans come to fruition.

- I regularly imagined the worst things that could happen and ranked them in order of terribleness. I then pictured it happening right now. I pictured myself accepting the turn of events indifferently and imagined myself responding to the challenge with a strength of character.

- I employed the Stoic Fork as described above when discussing challenges with others. I also prayed the Serenity Prayer, a Christian version of the Stoic Fork.

- Whenever I dealt with anger or one of the other seven capital sins, I tried enacting some advice from Epictetus, namely taking time out to allow myself to think through the situation rationally—cognitive distancing. I also tried modeling myself after others who had their act together better than I did.

- Percentage control appraisal—I rated a situation that was bothering me according to how much control I had over it, from zero to 100 percent. I focused on controlling what aspects of the situation I could.

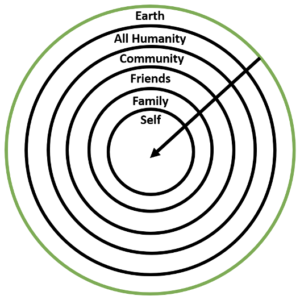

The Circles of Hierocles - I reimagined my relationships according to the Circles of Hierocles. You and your body are a point in the middle of several circles radiating outward. You gradually expand your connection to these other circles in your mind, increasing your feeling of affection. The goal is to love everyone as much as possible, accepting that they are changeable and that both they and you will die one day. The idea is to avoid unhealthy attachment to anyone or anything.

- Several times a day I actively remembered that I, too, will die one day; all of this is passing. This mindset exercise is called Memento Mori.

My take on stoic exercises

Stoic exercises are superior to positive thinking. Stoic thinking diminishes anxiety; positive thinking increases it. Dissonance exists between what you can see and what you wish was true when you regard things from a positive perspective. That causes positive thinking to subtly increase anxiety, especially when there’s a glaring difference between what you can see with your own eyes and what you fervently wish was true.

The ancient world was a tough place. They were busy hammering out basic ideas that we’ve taken for granted: government, medicine, construction techniques. And so on. Could it be that positive psychology is simply a product of a softer time?

I feel a sense of peace with a Stoic mindset. I strive for excellence within the boundaries of what I can control.

With Stoicism, whatever happens, you’re focused on what you can control about the situation and what the virtuous action would be. That makes you happier because virtue leads to happiness.

Whether it’s good fortune or bad, the stoic mindset is oriented toward happiness and prosperity no matter what.

On the other hand, with positive thinking/psychology, if you have lousy fortune and you follow one of the positive thinking writers, well, you didn’t do it right. You didn’t pray right or visualize success in the right way.

That $1 million you’d like in the lottery? Imagine it better, and the universe will supply it to you. It’s that simple.

And no, there’s no exact formula for attracting the jackpot no matter how many times some of these writers and proponents write “scientific.”

After my week of stoic exercises, I’ve regarded positive thinking, as advanced by Tony Robbins, Norman Vincent Peale, Napoleon Hill, and others, as almost dumb. Almost, because it does well for one to consider both sides of the coin, the positive and negative. They’re only getting to one side. Further, there’s no temper for those inherent vices of human nature. For them, greed is generally good (even if they say to give your favorite charity a cut, a kind of “finder’s fee” to pay toward being a good person).

For the stoic, greed is a weakness, a moral failing.

Same with lust, envy, overeating, or anything else like that.

It makes sense to diminish weaknesses as much as possible.

For further reading:

Who were the Stoics, and what was Stoicism?

Differences and similarities between Stoicism and Christianity

How to understand a dream about the death of a loved one

Your opinions form when you sleep and you should know what those opinions are

James Cobb RN, MSN, is an emergency department nurse and the founder of the Dream Recovery System. His goal is to provide his readers with simple, actionable ways to improve their health and maximize their quality of life.

This website uses affiliate links in some banner ads and text. If you click on a link and make a purchase, we may receive a commission.